Biography

Image credits »© Landesarchiv Berlin, F Rep. 290, Nr. 0081763 (Alois Bankhardt).

Image credits »© Landesarchiv Berlin, E Rep. 200-21 (Fotos), Nr. 1127.

Ernst Reuter and Berlin

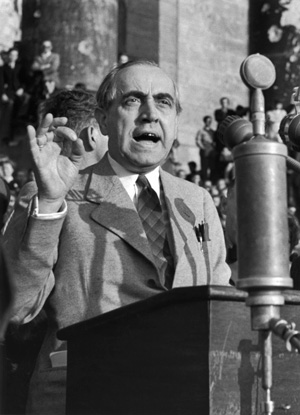

Ernst Reuter’s biography is uniquely intertwined with the history of Berlin. Anyone who wishes to understand the tumultuous story of this city in the twentieth century cannot avoid encountering him. Alongside Willy Brandt, he is one of the outstanding individuals who shaped developments after the Second World War. His important role during the Soviet blockade of the city in 1948 and 1949 has not been forgotten; during this period, Ernst Reuter became the Berliners’ most important voice for freedom and democracy. With his speech of 9 September 1948, given before the ruins of the Reichstag, he called upon the “people of the world” to support the city’s inhabitants in their struggle for self-determination. In a decisive moment, he gave expression to the population’s resolve to stand on the right side of history, to assert their own freedom, and to resist bending to Stalin’s will.

Ernst Reuter made a decisive difference during the crises of this period. Many years later, the American diplomat John J. McCloy honored Reuter’s service with the following words: “[h]e was a symbol of the steadfastness of the free world, when the fall of Berlin would have been a great catastrophe for the future of Europe”. Although the division of the city and entire country could not be prevented, Reuter saw West Berlin as an “island of freedom”. The city should stand like a beacon, shining through to the other side of the iron curtain and giving hope to those on the other side. The fate of the people of East Berlin and the GDR moved Reuter, and he called for understanding and solidarity on the part of the West Germans. 36 years after his death, when the Peaceful Revolution in the GDR finally overthrew the SED (Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands, Socialist Unity Party of Germany) dictatorship in 1989/90 and the path to reunification emerged, Berlin was once again at the center of events. Precisely what Reuter and other politicians had hoped for several decades ago came to pass: Berlin was the key to the solution of the German question, and the bridgehead to freedom.

But Ernst Reuter did not originally come from Berlin: he was a “newcomer”. He was born in 1889 in Apenrade (now Aabenraa), a small harbor town on the Baltic Sea that has belonged to Denmark since 1920. Sound recordings of Reuter’s voice clearly betray his North German origins. As a young man, shortly before the outbreak of the First World War, he came to Berlin in the hope of pursuing a professional and political future in the political, cultural, and social center of the German Empire. Like many others, it took him a little while to get used to the rough charm of the metropolis. “I find Berlin itself highly unpleasant,” he wrote in a letter to his parents: “It is full of dust and an appalling amount of people, all running around as though a minute costs them 10 Marks.” Despite this unfavorable first impression, the city would become a focal point in his life.

Image credits »© Landesarchiv Berlin, F Rep. 290, Nr. 0000846_C (Horst Siegmann).

Traces in the city

Numerous traces of Ernst Reuter can be found throughout Berlin. Sooner or later, anyone who lives here or visits for a few days is bound to encounter them. In many places, Reuter is directly commemorated: a large square in Berlin’s City West, near to the Zoologischer Garten train station, bears his name, as do a thermal power station, a concert hall, a school, a youth hostel, and a pleasure boat that carries families across the rivers and lakes of the area on summer weekends. The Free University of Berlin, which is steeped in tradition, celebrates “Ernst Reuter Day” each year in memory of the politician’s important contribution to its founding. Throughout the city there are commemorative plaques, memorials, and even an Ernst Reuter lime tree, which stands on the Great Star in the Tiergarten park. The tree was the first to be planted by the then Lord Mayor as part of the reforestation of the extensive park. The “green lungs” of the city had suffered severe destruction during the Second World War, and the replanting effort therefore symbolized hope for a better future.

This side of the “blockade Mayor’s” work is still generally well-remembered. The fact that Ernst Reuter was already active in the 1920s as a city councilor for transport, however, is hardly known. The expansion of the U-Bahn network and the founding of the former Berliner Verkehrs-Aktiengesellschaft (BVG) would hardly have been possible without him. With his transport and city planning, Reuter made a significant contribution to the capital city’s adaptation to the demands of modern life. Today, Berlin’s local public transport network is used by three million passengers each day. Most of these passengers have no idea whom they have to thank for the origins of their generally effective transportation network.

Image credits »© Landesarchiv Berlin, E Rep. 200-21 (Fotos), Nr. 564.

Image credits »© Landesarchiv Berlin, F Rep. 290, Nr. 0048721 (Gert Schütz).

Local politicians in the “age of extremes”

Anyone who studies Ernst Reuter will encounter a talented and versatile politician who was exceptionally committed to the concerns of the people in his city. But it would do him a disservice to reduce his life merely to these aspects. Beyond local politics, the major turning points of the last century were concentrated within his biography, reflecting not only the fate of Berlin but also the “age of extremes” (Eric Hobsbawm). Reuter came to understand the nature of totalitarian regimes as well as the value of liberal Western democracy. The extent to which the twists and turns of the early twentieth century were intertwined with Reuter’s life is illustrated by the fact that he knew Lenin and Stalin personally, and later met with President Dwight D. Eisenhower in the White House as a spokesman for “free Berlin”.

While Ernst Reuter initially found his way into the Social Democratic Party of Germany (the SPD) as a young man, his experience of the Russian revolution in 1917 led to his political radicalization. After a period as a supporter of the Bolsheviks and as a communist, he returned to social democracy at the beginning of the 1920s. He remained firmly attached to the SPD, but was never a “party soldier”, retaining a critical and independent spirit.

From 1931 to 1933, Ernst Reuter was Lord Mayor of Magdeburg. As the city’s leader, one of his greatest challenges was to combat the effects of the global economic crisis. In March 1933, soon after the National Socialists came to power, Reuter was forcibly ousted from office. Under the new regime, he belonged to the group of people who would be subject to persecution. He was arrested by the Gestapo and taken to Lichtenburg concentration camp twice. He eventually managed to escape from Germany, and from 1935 to 1946, he and his family found refuge in Turkey. Here, Reuter witnessed the far-reaching program of reform implemented by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, who wanted to sweep away the traditions of the Ottoman Empire in a “revolution from above” and modernize his young country. Ernst Reuter made his own contribution to these changes as an advisor and university lecturer in the field of urban development. He trained an entire generation of administrative experts, government officials, and urban planners, and is still highly respected in Turkey for this work today.

After returning to Germany, Ernst Reuter brought Berlin’s unique situation onto the stage of global politics. At the end of the 1940s, the city became the hotspot of the Cold War. Here, the interests of the two superpowers, the USA and the Soviet Union, clashed – and with them the two opposing social systems and values of West and East. Decisions that were made in Berlin had global repercussions, and the political climate in turn influenced the situation in Berlin. At the start of the 1950s, Ernst Reuter was regarded as one of Germany’s most prominent politicians by contemporaries in Washington, London, and Paris. Numerous trips abroad, during which he championed the interests of his city, earned him his reputation as “foreign minister” of Berlin. He appealed for support and for confidence in Germany’s citizens; just five years after the end of the Second World War, and in the shadow of the unspeakable crimes that had been committed under Hitler, this was not something that could be taken for granted.

Image credits »© Landesarchiv Berlin, F Rep. 290, Nr. 0011319 (Bert Sass).

Image credits »© Landesarchiv Berlin, F Rep. 290, Nr. 0008967 (Bert Sass).

Service to the community

But what did the Berliners themselves think of their Mayor? Of course, we could hardly hope to find one common denominator among the views of so many people, but the holdings of the Berlin State Archive contain thousands of letters that were addressed to Ernst Reuter by the citizens of Berlin. Placed alongside other documents, they paint the image of an extremely popular Lord Mayor. Time and again in these letters, we find Reuter described as a “father” to the Berliners. His veneration was partially due to the fact that he regarded his work as a form of service to the city’s people. With the moral compass of a social democrat and remaining true to his own principles, he was also adept at distinguishing between what was desirable and what was possible in politics. He did not hide behind rhetoric but named existing problems in a language that was clear and generally accessible. When confronted with the opinions and arguments of others, Reuter showed himself to be open-minded and respectful, even if they did not correspond with his own views. As early as 1931, he declared in a radio address that every municipal leader should understand their task as that of “bringing together conflicting elements to cooperate in the common interests of the city in their charge”.

Reuter saw himself first and foremost as a local politician. For him, working for and in the local community was not a secondary matter that should take a back seat to Politics with a capital ‘P’: on the contrary, it represented the essence of political action. He gave people constancy, orientation, and confidence in difficult times, and his approachable manner inspired great trust. Willy Brandt later called it a “stroke of luck” that Reuter had steered Berlin through the post-war period: “[h]is expertise and his nature enabled him to make the best of difficult but challenging situations”.

The extent to which Ernst Reuter was venerated by the citizens of Berlin was made powerfully clear in September 1953: when news of Ernst Reuter’s death became known, a deep sadness spread throughout the city. On the day of his funeral, hundreds of thousands of people lined the streets to pay their last respects to “their” Mayor.

(This text is based on the introduction by Michael C. Bienert in Ernst Reuter: A Mirror on Berlin, Melbourne 2021. The title, as well as the German translation, are available from the publisher Ueberschwarz.)

↑ Image credits Headerimage© Landesarchiv Berlin, E Rep. 200-21 (Fotos), Nr. 564.